Michael Kane's

Twitter led me to an article published the other day in the Journal of

Experimental Psychology: General, entitled Any Effects

of Social Orientation Priming on Object-Location Memory Are Smaller Than Initially

Reported. For the record, (a) I admire Michael Kane's work, (b) JEP:G

is a very respectable journal in the field of experimental psychology, and (c) in case

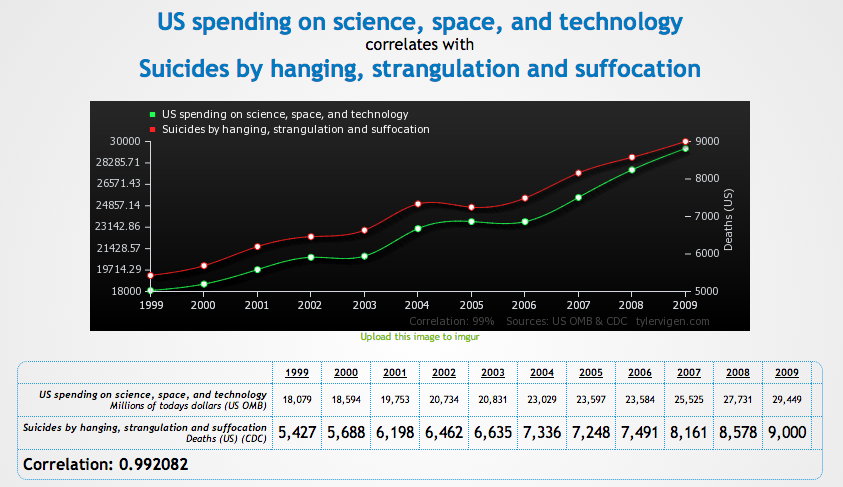

this is your first day on the Interwebs, psychology -- and especially social psychology

-- has suffered a tremendous reputational damage in the past couple of years. Just

google "psychology replication crisis" and you'll get tens of thousands of examples of

academics, pop-sci journalists, reasonable skeptics, and the inevitable ranters

explaining the Reproducibility

Project, p-hacking, questionable research practices, retractions, and

so on and so forth. The gist of the story is that many results in the psychological

sciences published as (and consequently claimed to be) "real", that is, statistically

reliable and thus representative, have been found to be nonreplicable, i.e., they don't

stand up to scientific scrutiny. Which is bad enough in itself, but the real problem

behind this whole crisis is that failures to replicate published results (regardless of

whether they were conducted out of curiosity, spite, or something in between) rarely

make it through the peer-review process, with debatable justifications like "This

doesn't add anything new" or "But wait... This has been shown before so you must be

wrong!" (the wording here is paraphrased and based on anecdotal evidence, mind you). Now

I leave the politics involved in that up to the reader's own interpretation, but a very

immediate effect of this behaviour (and I bet it has a huge effect size) is that labs

all over the world will waste a lot of time and money on trying to replicate result XY,

simply because they have no way of being aware that many other labs have tried and

failed before them. This actively delays scientific progress, and both frustrates and

disillusions those involved.

It is for this reason that I applaud JEP:G's decision to set an example and publish a

study (including four experiments conducted with 438 participants) which failed to

replicate results published in 2002 and 2009. While its topic -- the influence of social priming on

cognition -- is entirely beyond my expertise (and I would have no way of knowing about

potential rivalries between the authors), I consider the effort to question extant

evidence, and the subsequent gratification of a high-rank publication a huge step in the

right direction. Psychology, like any other science, should be critical, and there

should be reasonable outlets for new findings -- because not finding what others found

is a finding as well.

Faith in academia restored for today. Over and out.